Lossless Audio: What Spotify Didn’t Tell You About What Really Makes a Difference

From: Vitor Valeri

Illustrative image of Spotify hiding information so users won’t know (Image: Vitor Valeri/Hi-Fi Hub)

Illustrative image of Spotify hiding information so users won’t know (Image: Vitor Valeri/Hi-Fi Hub)

Spotify has begun to offer lossless audio on its music streaming platform, as reported by Hi-Fi Hub. Although most people believe that a FLAC file at 24 bits/44.1 kHz will bring a fundamentally new listening experience, the reality is different. The improvement in sound quality after this change will be small, as demonstrated in the article that explains what high-resolution audio is.

There are, however, factors that can truly make a considerable difference in how sound is perceived in music. One of them is the process by which music is delivered to streaming services, also known as DSPs (Digital Service Providers). In addition, there is the issue of the large variation in the level of “perceived loudness” in tracks produced over recent decades, as well as the application of loudness normalization.

The influence of the music delivery process on the audio of music streaming platforms

According to Pablo Alonso Jiménez in his article “Automatic detection of audio problems for quality control in digital music distribution”, presented in 2019 at the 146th AES (Audio Engineering Society) Convention in Dublin, Ireland, artists often face difficulties in delivering their music without the assistance of third parties, making it necessary to rely on music distributors, which may be:

• Digital distributors: responsible for transferring music to streaming platforms and online stores.

• Licensing services: responsible for licensing activities for record labels and independent distributors.

• Record labels: in addition to producing recordings, they also provide distribution services.

The major problem arises with small and independent music distributors, as Jiménez explains in his article:

“Small and independent distributors are not able to develop their own technology to manage their catalogs, deliver releases to Digital Service Providers (DSPs), and collect their royalties. To provide these services, there are white-label software-as-a-service (SaaS) platforms, such as SonoSuite.”

According to Pablo, music distribution services not only help bring artists’ music to more platforms but also play an important role in maintaining a high quality standard for the tracks delivered to streaming services. Jiménez states that, in order to achieve this, it is necessary either to use a catalog management program or to perform quality control manually, which is more time-consuming.

The major drawback of performing quality control manually lies in the potential audio problems that may occur. To facilitate their identification, Pablo divided each type of problem into five categories:

• Inadequate silence margins

• Stereo problems

• Digital audio artifacts

• Loudness (perceived volume) problems

• Noise problems

Jiménez says that silence margin issues usually appear due to human error during the rendering process, and may result in excessive or insufficient silence at the beginning or end of a track.

Pablo explains that stereo problems occur due to improper management of audio channels, which may include:

• “Fake stereo” (for example, when the same channel is configured twice in the master output or when an old mono recording is digitized using a stereo configuration).

• Phase problems (when channels are strongly out of phase, causing musical components to be lost on certain playback systems).

According to Jiménez, the presence of artifacts in audio files causes playback not to correspond to what was originally recorded. He states that artifacts may arise during the copying process to storage media such as HDDs or even CDs. Below are examples of artifacts mentioned by Pablo in his article:

• Gaps: silent segments of audio where the signal drops to zero or becomes stuck at a certain value.

• Clicks and pops: impulsive noises that may originate from various causes, such as plosive sounds in vocal recordings or artifacts introduced during digitization processes.

• Waveform discontinuities: abrupt and unnatural jumps in the waveform, which may be caused by the loss of waveform samples or by improper transitions (crossfades) between tracks.

• Noise bursts: sequences of artificial samples, usually originating from errors in the encoding process.

• Clipping: when the waveform amplitude exceeds the available dynamic range.

The problem of perceived loudness, which can be measured in LUFS (Loudness Units Full Scale), as well as saturation, occurs due to improper use of compression or limiting, according to Jiménez. This issue will be discussed in more detail later.

Finally, Pablo mentions noise problems, which are stationary processes present throughout the entire track. Jiménez divides them into two types:

• Humming tones: low-frequency, narrow-band noises usually caused by the power grid (in the 50–80 Hz range).

• Broadband noise: includes a variety of noises, such as vinyl crackle or the inherent hiss of electronic devices.

To address these problems, Pablo Alonso Jiménez proposes the use of “algorithms developed or adapted for the detection of the described audio problems.” Jiménez states that these algorithms “are publicly available as part of the open-source Essentia library,” and that their source code can be consulted on GitHub.

Variation in perceived loudness in music and “loudness normalization”

Tidal partnered with Eelco Grimm to conduct a study on volume normalization (loudness normalization) and perceived loudness in music through measurements in LUFS [1].

In his article “Analyzing Loudness Aspects of 4.2 Million Music Albums in Search of an Optimal Loudness Target for Music Streaming”, presented in 2019 at the 147th AES Convention in New York, United States, Eelco Grimm analyzed tracks from the Tidal streaming service to determine the variation in LUFS levels in music over recent decades, as well as to distinguish two types of volume normalization applied by streaming platforms.

According to Grimm, streaming services “have a centralized infrastructure and develop their own applications,” which allows “all music in the service catalog to be normalized in terms of loudness at once for all users.” By doing so, Eelco states that the listening experience can be improved and that it may contribute to “the end of the loudness war.”

Doing the same with CDs is impossible, since there is no centralized service responsible for processing and standardizing the loudness of all albums. However, through the ITU-R BS.1770 recommendations [2], LUFS meters have become a standard tool in major digital audio workstations, according to Grimm.

[1] LUFS (Loudness Units Full Scale) is a way of measuring perceived loudness by taking into account how humans perceive sound (for example, emphasizing midrange frequencies, where the human voice is located, over bass and treble). The higher the LUFS value, the louder the sound. For example, −5 LUFS is louder than −10 LUFS.

[2] The ITU-R (International Telecommunication Union) BS.1770 recommendations provide objective methods for measuring audio loudness using LUFS (Loudness Units Full Scale) and LRA (Loudness Range), among other metrics.

Volume normalization

The volume normalization feature was created in 2001 by David Robinson through the development of an open standard called ReplayGain, which allows music players to keep individual tracks and entire albums at the same volume using metadata that describes the electrical (analog) signal of the file.

The use of metadata has the advantage of leaving the original audio intact. In order to measure loudness through electrical signals, ReplayGain uses its own psychoacoustic algorithm. ReplayGain was adopted for ID3 metadata and for the metadata of the Ogg Vorbis format, which is used by Spotify. The popular streaming application uses loudness normalization by default based on ReplayGain.

Apple developed its own volume normalization technology, which it called “Sound Check.” It uses a proprietary psychoacoustic analysis algorithm. This feature is not enabled by default in its streaming service, Apple Music. It is worth noting that both ReplayGain and Sound Check emerged before the ITU-R BS.1770 recommendations.

According to Grimm, Tidal adopted ITU-R BS.1770 because it is an open and globally recognized standard for audio loudness measurement.

Types of volume normalization in streaming services

Volume normalization can be applied in two ways: track normalization and album normalization. Streaming services must choose between these two approaches.

In track normalization, each track is individually adjusted so that all music plays at the same loudness level. Since music is mastered as a complete album, where the loudness relationships among tracks are carefully balanced, this is not the best choice. By applying track normalization, the decisions made by the mastering engineer are destroyed.

Album normalization may be a solution, although it still becomes problematic when playing playlists that include tracks from different albums. In album normalization, all tracks within an album receive the same gain during playback.

According to Eelco, Spotify alternates between track normalization and album normalization based on user behavior. In contrast, Grimm explains Tidal’s approach as follows:

“When the research for this article began, Tidal had only prepared track normalization and decided not to enable it by default in order not to interfere with the artistic intent of mastering engineers.”

Grimm explains that there are two types of album normalization: one based on the average loudness of all tracks and another based on the loudness of the loudest track in the album. ReplayGain uses the average loudness approach. However, Eelco notes that this method can be abused if an album contains one very loud track and several very quiet ones, which would prevent the end of the loudness war.

Album normalization based on the loudest track uses the loudest song as the reference for the rest of the album. This causes the quieter tracks to be adjusted to the same level as the loudest one. The advantage of this approach is reflected in music production, as artists know the loudness target of all tracks once the first (loudest) track is completed.

According to Grimm, Tidal preferred the album normalization method based on the loudest track.

Reference for loudness measured in LUFS

According to Eelco, due to CENELEC hearing-safety regulations (EN 50332), DAPs (Digital Audio Players) and mobile phones sold in Europe are limited to −10 LUFS at 100 dBA. Therefore, AES Recommendation TD1004 for “Loudness of Audio Streaming and Network File Playback” suggests maintaining volume levels in the range of −20 LUFS to −16 LUFS when listening to music on portable music players.

Results of LUFS measurement analysis using Tidal’s music catalog

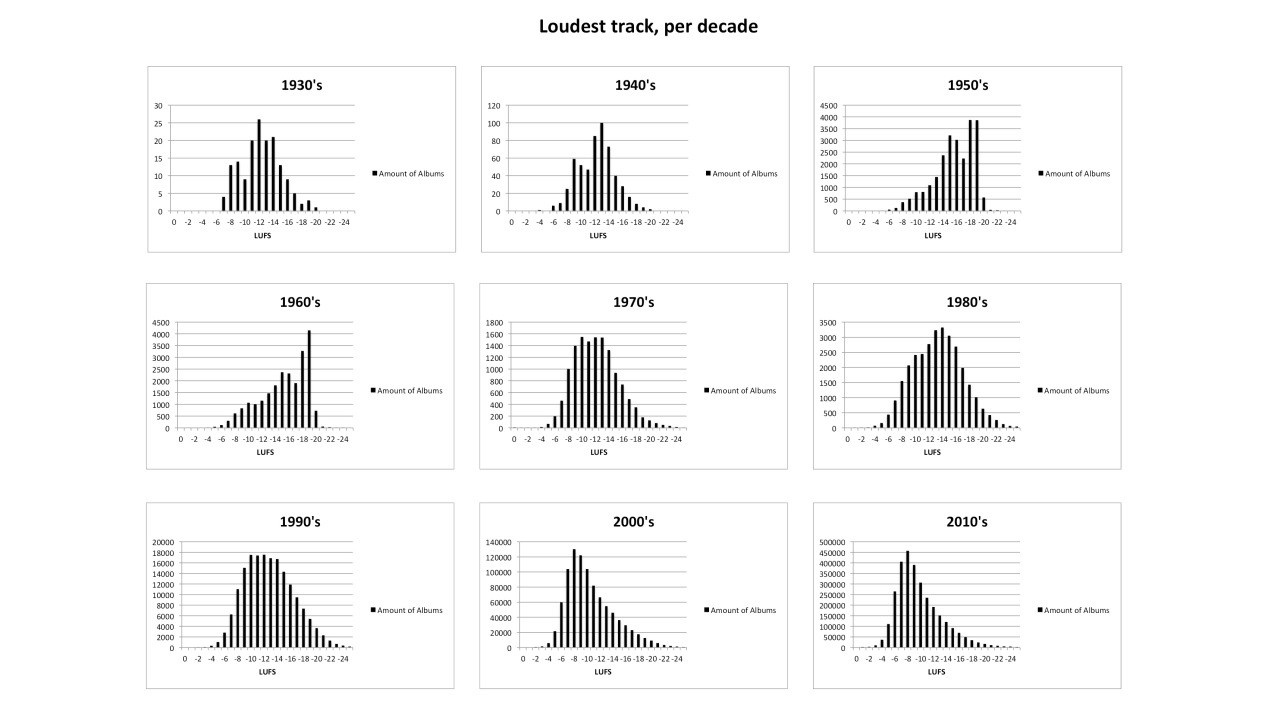

Eelco Grimm’s study made it possible to generate histograms of Tidal’s music by decade, starting in the 1930s and extending to the 2010s. From these images, it is possible to observe a clear trend toward increasing loudness in tracks, confirming the emergence of the “loudness war.”

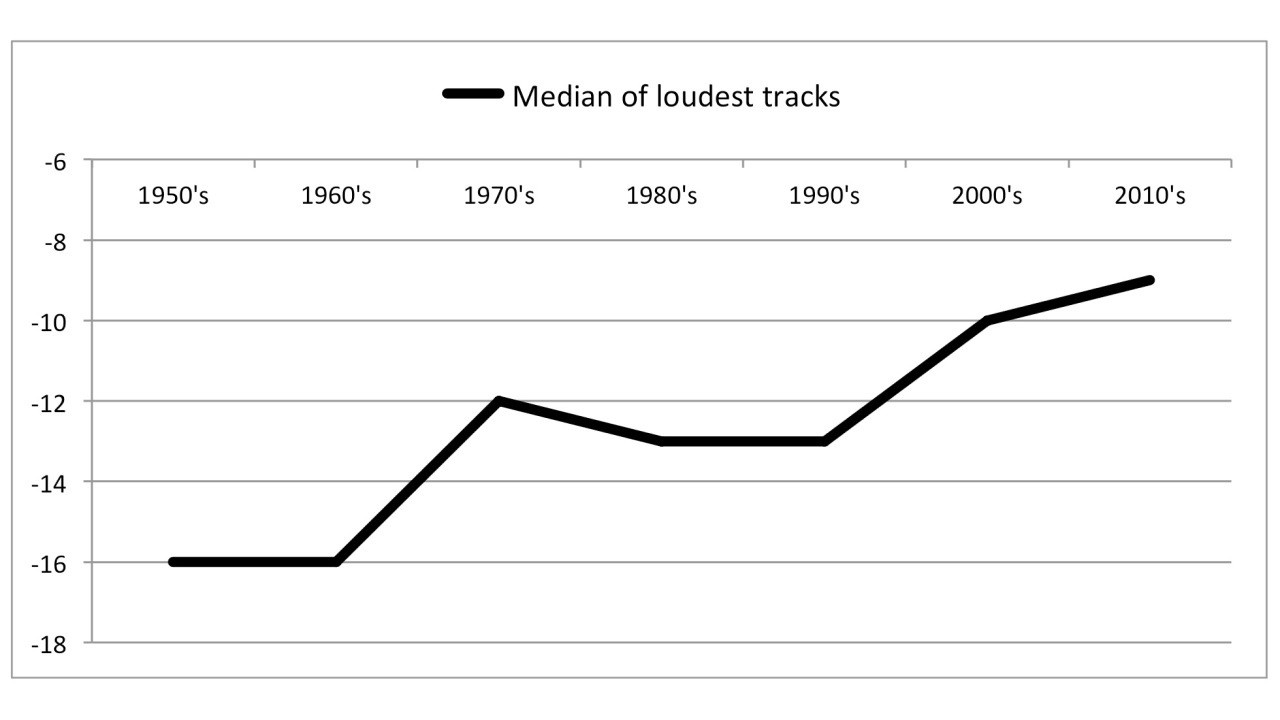

To further clarify this, Grimm generated a graph showing a curve of the average LUFS levels of the loudest tracks by decade. Eelco states:

“The median increased from −16 LUFS in the 1950s to −9 LUFS in the 2010s. In the 1990s, the median was still −13 LUFS.”

During the analysis, Grimm found that “the release date metadata (on which these graphs are based) often do not reflect the original release date,” and that “they frequently indicate the release date of a remaster or even the date the album was added to the database.” However, Eelco emphasizes that this issue is not Tidal’s fault, but rather that of record labels, which provide this information.

Even with these inconsistencies in metadata, Grimm explains that “there are enough albums from multiple decades to draw conclusions.” He states:

“The 1950s and 1960s, for example, both have more than 20,000 albums. Note that the mode of −19 LUFS in the 1950s and 1960s is due to an above-average presence of classical and jazz music albums during that period.”

Eelco also shared information on LUFS measurements for certain genres, providing another perspective on music production over the decades:

“165,649 albums with ‘Classical’ metadata were analyzed: the mode of the loudest track distribution was −17 LUFS, and the median was −16 LUFS. For 287,722 albums with ‘Jazz’ metadata, the mode was −12 LUFS and the median was also −12 LUFS. For 473,557 albums with ‘Pop’ metadata, the mode was −8 LUFS and the median was −9 LUFS.”

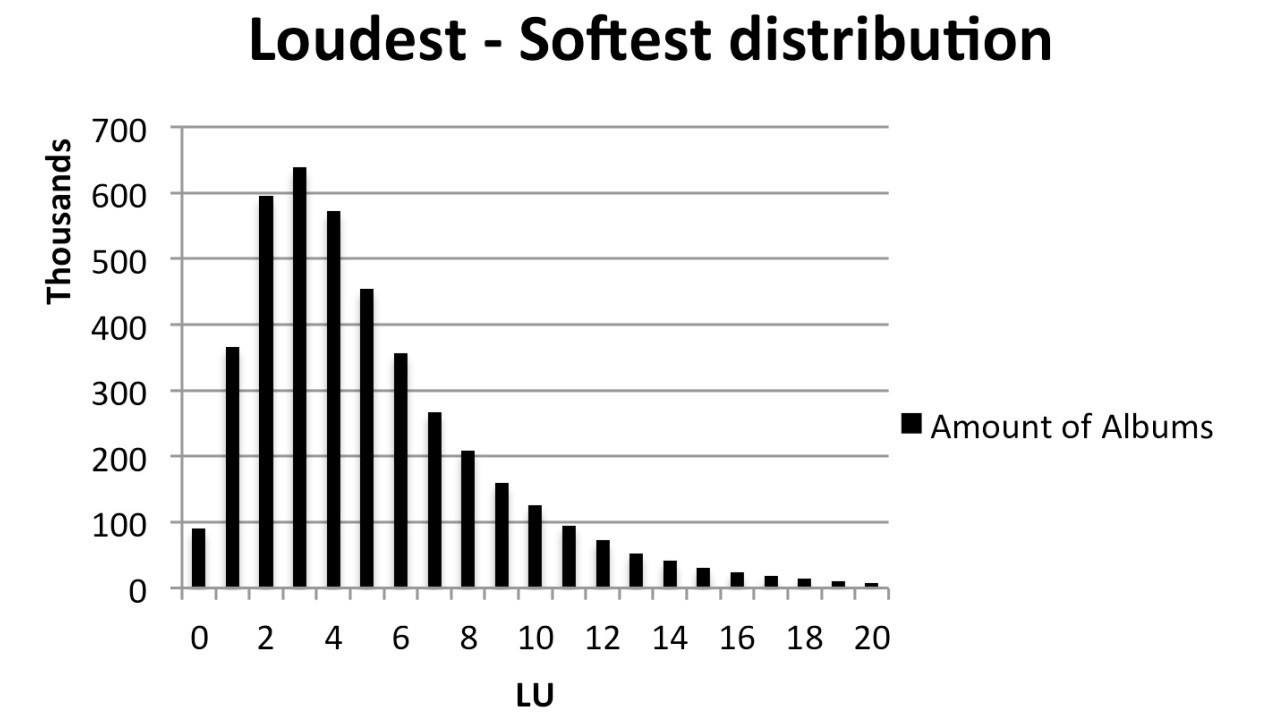

Finally, Grimm presents a graph quantifying the LUFS difference between the loudest and the softest tracks of all albums.

Eelco explains:

“The median in this graph is 4 LU, and the mode is 3 LU. This means that in 50% of all albums, the mastering engineer created a difference of 4 LU or more between the loudest and the softest track. In only 2% of all albums are the softest tracks less than 1 dB below the loudest ones. In other words, always using track normalization would affect the intended loudness balance between tracks in 98% of all albums. This does not seem to serve artists well.”

Conclusion

Although Spotify has added lossless audio to its streaming platform, there are still several issues to be resolved regarding the music being added to its catalog. Furthermore, there are problems related to the volume normalization feature, which is enabled by default in its applications. Because gain is applied on a per-track basis, it ultimately destroys all the mastering work performed on albums.

Tidal is still affected by issues related to music production and by metadata errors caused by distributors. However, when normalization is enabled, it is applied on an album basis using the loudest track as the reference, which is a more intelligent alternative and tends to preserve the artistic intentions of music producers and mastering engineers.

Share:

No comments have been made yet, be the first!